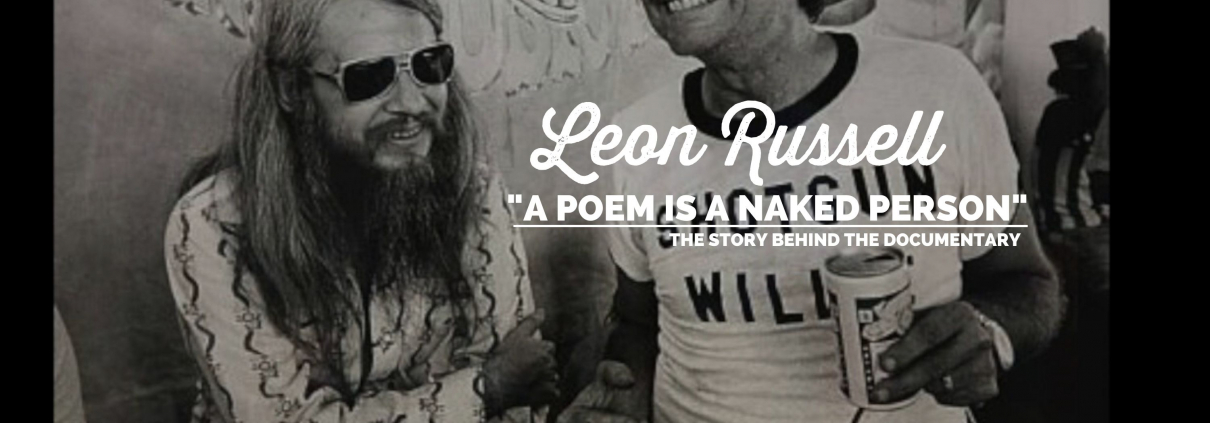

Leon Russell and his Lost Documentary

Leon Russell is a music legend and perhaps the most accomplished and versatile musician in the history of rock ‘n roll. In his distinguished and unique 50 year career, he has played on, arranged, written and/or produced some of the best records in popular music.

Ask Leon Russell a straight question — say, about the documentary made about him in the early Seventies that’s just now seeing the light of day — and the iconoclastic singer-songwriter’s answer will eventually wind its way back to the subject after rambling down the crookedest of backroads. “We had a guy at the studio at the time, a harmonica player,” he begins. “And one day he put a mic on his heart and started playing harmonica. He played more and more as his heartbeat got faster and faster, until he finally passed out.” Russell pauses, eyes unseen behind mirrored sunglasses as he sits in a hotel lounge. “Kind of a weird story. I don’t know the reason why I thought of that. But it’s kind of like that movie.”

Actually, he’s not that far off. A Poem Is a Naked Person, which reaches theaters for the first time nearly 43 years after it started filming, is the sort of free-form rock doc that’s happy to follow whatever catches the camera’s eye. Made while Russell was recording demos for his rowdy 1973 album Hank Wilson’s Back, the movie captures the musician playing several fever-pitched shows and jamming with the cream of Nashville’s session-player crop; George Jones and Willie Nelson stop by for a few jaw-dropping cameos. But it’s also the type of fly-on-the-wall portrait of an artist that’s likely to cut away from performances mid-song to visit Russell’s eccentric neighbors, attend a building implosion in downtown Tulsa, and watch a snake swallow a chick whole. “It looks more like a travelogue than a Leon movie,” the singer says.

The project started back in the early Seventies when filmmaker Les Blank (The Blues Accordin’ to Lightnin’ Hopkins) and his assistant Maureen Gosling had an offer from Russell’s then-partner Denny Cordell to make a documentary on the Oklahoma-based songwriter. Having just finished a shoot, the couple were in need of another project; soon, they found themselves setting up shop on Russell’s lakeside compound, in a studio previously purposed for something called “Pappy Reeve’s Floating Motel and Fish Camp.” They wound up staying for two years, working through cuts of the film and springing to action whenever folks came over to play music. “He had this huge editing lab set up in one of the floating hotel rooms,” the musician says of Blank. “It was true hippie stuff all the way down the line.”

The now 73-year-old musician starts tugging at his long, wispy beard before launching into an anecdote. “I remember an instance up there at the lake, Bob Dylan came up to visit me,” he says. “I took him out in my boat, and then I came back to get some gas from this little old lady. She walked up, looked at Bob and pointed at me and said, ‘Do you know this guy’s famous all over the world?’” Gosling, sitting across from him, giggles at the punchline before remembering the visit from a different vantage. “[Dylan] didn’t want to be filmed because he was out in the country — he figured he was away from all the hubbub. I remember going into the control room in the studio and he was hiding behind the door. Les said it felt like having a butterfly on his tripod, being unable to film Bob Dylan.”Production shifted to Nashville when Russell went to cut Hank Wilson’s Back!, in which Dixieland’s finest session musicians were corralled to record, according to the musician, a whopping 27 songs in two-and-a-half days. A former studio pro, (he’d already backed the likes of Sam Cooke, Frank Sinatra and the Rolling Stones), the singer felt comfortable working at a breakneck pace; in turn, Blank was energized by all that kinetic energy. “He was good at what he did…he was just kind of a jerk sometimes,” Russell says, hinting at the animosity that would eventually stall the project for decades. “But I guess I was kind of a jerk too.” Gosling concurs on both counts. “There were a few times when Les was really belligerent when he was drinking,” she says. “But you were not easy either.”

It was around this time that tensions arose from hard living and personal conflict; when asked why he and Blank never spoke over the years, Russell says “I didn’t want to take the chance that I might have killed him.” Ultimately, however, it was simply creative differences that kept Poem out of the public eye. While Russell was hoping to have more of his story and songs front and center, Blank’s strategy, according to Gosling, was “to film around the subject. The environment the person was living in, their memorabilia on the walls, photographs…things like that.”

But Russell wasn’t buying any of it — especially because he was already paying for it. “I thought it was more of a movie about him than it was about me,” he says. “But I never wanted to lose control over it. For one thing, I had $660,000 in it. The other thing was that I thought it might be of value in the future.” The film was caught in legal limbo after Russell broke from Cordell, and the singer even put the kibosh on Blank’s occasional free screenings of the film at schools and museums. According to the filmmaker’s son Harrod Blank, Poem lived for years “in cardboard boxes that were dust-ridden in Les’ closet.” Though he had physical possession of the film, there was no way of having it seen. “It was like an old car that you loved but it doesn’t run,” Harrod says. “And a car’s nothing if it can’t drive.”

Shortly before Les Blank died of cancer in 2013, Harrod reached out to Russell on Facebook, asking for permission to screen Poem one last time. “I think he had probably put it out of his mind,” Harrod says, describing Leon’s attitude toward the film. “You know — ‘That’s not something I’m ever going to touch again.’ Then when Les died and I came back around, he was like ‘This kid wants to do all this, he’s going to spend money, he’s going to do all the legal? Okay, I’ll take a look at it.’” Motioning to Harrod, Russell says, “I met this guy and I quite liked him more than I liked his dad.”

It wasn’t the first time Harrod tried to do something with the film. Back in the late Eighties, he was on the verge of making a movie for Miramax in which the old footage would be intercut with the performer’s more recent shows. “I talked to Les and he blew up, and said there’s no way you’re doing anything with this movie. He didn’t want to compromise,” he says. “If Leon said Les, I really don’t want to be swearing in the movie, [my dad] would have taken it personally,” Harrod says.

“And added more curse words,” Russell interjects.

Once Janus Films, who’d released several of Les Blank’s films on DVD under their Criterion Collection imprint, expressed interest in distributing Poem, there was a stipulation that Blank’s vision be left intact (beyond a few minor tweaks and a swapped-out a song for clearance purposes). Which meant that Russell would finally have to put all of his reservations aside. Though he would still prefer to delete a terse scene with songwriter Eric Andersen, and indeed lose all of the cursing and smoking, he doesn’t dispute the film’s accuracy. “That’s what I did,” Russell says, leaving it at that. And after a successful premiere at this year’s SXSW Film Festival, it appears the artist has finally made peace with the project.

And for all of their animosity, it’s clear that the elder Blank and Russell were kindred in their fundamental impulse to collect: people, experiences, and extravagant weirdness. “I see stuff in antique stores and it calls my name — I have to have it.” He talks of spending $2800 on a wall-mounted tiger head decorated in polyester hair follicles, and trying to flip a 1989 Cadillac Fleetwood; Blank’s filmography is a butterfly net of musicians, madmen, gastronomes and roadside Americana. “He was a collector of the unusual,” Russell says of the man he avoided for 40 years — the same man whose testament to the singer’s cracked genius is finally seeing the light of day. “Me being the prime unusual beast.”

To read the full article from the Rolling Stone article by Eric Hynes on July 2, 2015 click HERE

Here is George Jones in the studio (an exerpt from “A Poem is a Naked Person” documentary